Catherine Hokin examines how the Nazi propaganda machine twisted language to hide mass murder, including their Aktion T4 euthanasia programme.

Language and how it is used is particularly important to a writer. That might sound very obvious but it is a truism I have come back to again and again while writing fiction based around World War Two, and it is particularly significant for my latest novel Her Last Promise, which is the final book in the Hanni Winter series.

Using language to cloak reality was a key tool of the National Socialist propaganda machine and euphemisms – such as using ‘cargo’ to describe what was being moved during the deportations instead of the more truthful ‘people’ – were deliberately commonplace.

Holocaust survivor Nachman Blumental, one of the founders of the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland, made a study of this practice immediately after the war, authoring a glossary of what he referred to as ‘innocent words’ which had taken on hidden meanings.

His list includes terms such as ‘asocials’ and ‘showers’ and ‘resettlement in the east’ and draws attention to what has to be the worst of euphemism of them all: determining the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’.

As Blumental pointed out, only antisemites could come up with such a ‘dilemma,’ and then choose to solve it through the mass murders they referred to as ‘special treatment.’

All of the Third Reich’s public language was purposefully chosen. Some of it was intended to obscure its goals, some of it was used to prevent panic spreading, and some was intended to soften-up a wider audience in order to bring them around to a ‘correct’ way of thinking.

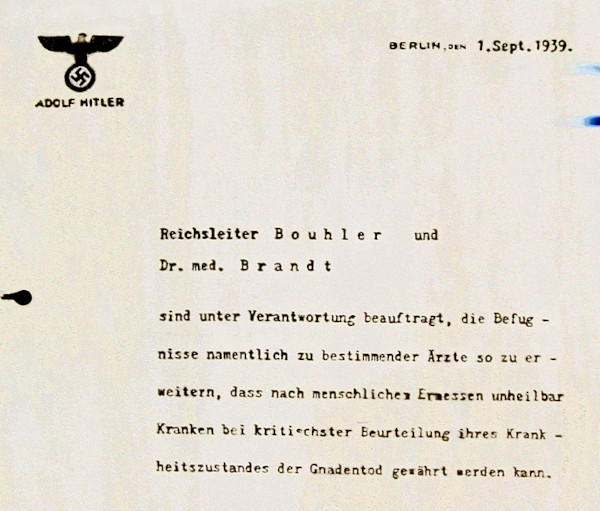

This usage was a particularly important feature of the Aktion T4 euthanasia programme, which features in my novel. The definition of euthanasia is the act of ending the life of a patient who is terminally ill and/or experiencing severe and incurable pain, with the sole intent of limiting further suffering.

Under the Third Reich, that definition disappeared and instead euthanasia became a blanket term for removing whole sectors of the population who were determined as having ‘no value’ and/or as threatening the ‘purity’ of the Aryan gene pool.

Between the passing of the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring in 1933 and the end of the war – and beginning with children – the Nazis extended the parameters of euthanasia to include anyone with any degree of mental or physical disability, those not of German or ‘related’ blood, and anyone who had been living in an institution (including old peoples’ homes and sanatoria) for five years.

It was a killing programme which quickly became industrialised: once lethal injections were dropped in favour of gassing at six specially equipped installations, it is estimated that between 250,000 and 300,000 people were murdered. And all of it was carefully hidden beneath a veil of lies.

Babies born with birth defects were catalogued so that they could be ‘helped,’ children with disabilities were sent for ‘special care.’ Death certificates sent to the families – when there were families who might ask questions – recorded their loved ones as having died of pneumonia or natural causes, and urns, not bodies, were returned. And when people did become suspicious as the grey vans rolled out of the hospitals, the propaganda machine cranked up another notch.

Two films were produced under Goebbels’ direction between 1939 and 1941 with the sole aim of encourage the belief among the German population that ‘mercy killing’ was a humane act.

Of the two, Dasein ohne Leben (Existence without Life) – which depicted mental illness as a threat to society and included distressing images taken inside hospitals – was the most overtly brutal and opinion is divided over how wide an audience it was actually shown to.

I haven’t seen it and only eight reels of it exist. I have, however, seen the second one, the unashamedly tear-jerking Ich Klage an (I Accuse). This stars the beautiful Austrian actress Heidimarie Hatheyer – a favourite of the Third Reich who was later found guilty of indirect complicity in the mass extermination – as a doctor’s wife suffering from multiple sclerosis who pleads with her husband to kill her.

It is packed with terms such as ‘right to die’ and ‘make the poor woman’s suffering less painful’ to describe her plea for a ‘dignified release,’ and includes a very long court case which pretends to debate the issues around her request and her husband’s consequent actions. It was one of the most profitable films made under Goebbels’ ministry, grossing over 5.3 million marks at the box office.

Whatever the actual reaction to the film – and we don’t know, because the only opinion polls collected were carried out by Goebbels’ office – protests against the T4 killings continued and, in 1941, the programme was suspended.

Except, of course, it wasn’t. Of the total euthanasia deaths recorded, three-quarters were carried out after the pretend suspension and the killings continued until the last days of the war. According to records, the last child to die under Aktion T4 was a boy by the name of Richard Jenne who died at the Kaufberen-Irsee euthanasia facility in Bavaria in May 1945, after the Americans had already occupied the town.

The T4 programme was named after the address of the office which administered it, which was located in the leafy and elegant Tiergartenstraβe in Berlin. The men who designed it, including Hitler’s personnel physician Karl Brandt, were medically trained.

The personnel who ran the gassing facilities – and the woman who administered Jenne’s injection – were doctors and nurses. They twisted their pledges to take care of their patients into something far more sinister. And the phrase they used among themselves to describe their victims, the chilling ‘useless eaters,’ is a far cry from the ‘mercy killing’ platitudes the Third Reich hid their murders behind.

Words have power, as writers and readers we know that.

But, as too much current political rhetoric proves, none of us can afford to get complacent. Gary Lineker may have got into hot water by pointing out that throwing around terms such as ‘invasions’ and ‘swarms’ and ‘criminals’ to turn people into others can have terrible consequences, but I for one was heartened by all the fans on the terraces holding their “I’m with Gary” banners.

And by the strength of that shared “I’m with”.

Her Last Promise by Catherine Hokin is published on 30 May, 2023. It‘s the fourth in her Hanni Winter series.

See more about this book.

Catherine has written several features for Historia about the history behind her novels. You may find these interesting:

Concentration camps and the politics of memory

The Minister for Illusion: Goebbels and the German film industry

The legacy of the village of Lidice

The ‘hidden’ Nazis of Argentina

The Berlin blockade, 1948–9: the first Cold War stand-off

Images:

- Moers Stolperstein Ruhrstraße 51 zur Erinnerung an Magdalena Hirtz, die… 1941 in Bernburg im Rahmen der “Aktion T4” ermordet wurde (‘stumbling stone’ commemorating Magdalena Hirtz, murdered in 1941): Lutz Hartmann for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

- Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren (‘Hospital and nursing home’ in Kaufbeuren), a euthanasia facility, 2 July, 1945: Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Hitler’s edict ‘granting mercy death’ to ‘incurable’ patients, 1 September, 1939: Nuremberg documentation centre museum, Marcel (Photographer) and MagentaGreen for Wikimedia (public domain)

- Still from Ich Klage an, 1941: Internet Archive (public domain CC0 1.0)

- Richard Jenne, last known victim of Nazi euthanasia programme at Kaufbeuren-Irsee Sanatorium, 31 July, 1941: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park via Wikimedia (CC0 1.0)