Does it matter whether King Arthur, or someone who the legend is built on, existed in history? For Nicola Griffith, author of Spear, it doesn’t. What was important when she was writing her book was to make a place and a voice for people who have been left out of the stories, and to create a Camelot where they were heroes.

When it was published nine years ago, Hild, my novel about the girl, then young woman, we know today as St Hilda of Whitby, was discussed by a not-insignificant number of critics as though it were fantasy. There is absolutely nothing fantastical in the novel – no gods or monsters, magic or miracles – and yet it was short-listed for several fantasy/science fiction awards. Clearly to many readers it felt like fantasy. Why?

Perhaps it was the sense of immanence running through the landscape, the wild wonder and exhilaration of a young person for whom so much is new discovering the joys and mysteries of the natural world.

Perhaps it was the rhythm of the prose, which I used in places to mirror the ripple of Brythonic poetry and in others to echo the heroic metre of Old English, the kind of rhythm and metre Tolkien borrowed to such great effect.

A more nuanced explanation could be that the representation of female power and autonomy in early seventh-century Britain – a young woman as the director and subject of her own life rather than the abused object of others – was directly at odds with many readers’ understanding of history.

If they believed it to be impossible then the story as written must be fantasy. This is implicit (and occasionally explicit) bias. And it originates in what we are taught about the past: in history.

History, though, is not fact, not What Actually Happened. History is the story we tell ourselves to try to make sense of what happened (or what we think happened) in order to make sense of today. The storytellers’ own experience, beliefs and cultural biases influence their interpretations of events. History is subjective, and therefore often wrong.

Historians accept this. History is constantly revised and reinterpreted. What was considered implausible 150 years ago by most documentary historians – for example, the existence of King Arthur or someone like him – became, with the work of archaeologists 80 years later, plausible. And 30 years after that, Arthur’s historicity returned to being sneered at. (Now, once again – at least among a tiny subset of historical linguists – the idea is beginning to regain respectability.)

When Rosemary Sutcliff wrote Sword at Sunset in 1963, acceptance of Arthur’s historicity was at its height. Few would have disagreed with a label of historical realism; now, most historians would.

On the other hand, most readers, who rarely keep up with the specialists’ changing perspectives, still believe what they learnt from outdated historiography: Arthur was real and, in his time, women were chattel.

This variable nature of historicity and historiography is why, with the release of my new book, Spear, I find myself in an interesting position.

The book is a blend of historical realism, legend, and fantasy. Paradoxically, the element that I consider the most important facet of its historical realism is the one that many readers may regard as the most fantastical.

Spear is set in early sixth-century Wales and is the story of Peretur, more usually known – since Caxton’s early 15th-century printing of Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur – as Sir Percival.

In terms of historical realism, the book’s material culture, such as building materials, weaponry, food, livestock, textiles; the physical and cultural milieu, such as travel logistics, climate change, social structure, religion, and ethnogenesis; and the language – with the major caveat that I’ve substituted early Welsh for Brythonic and had to essentially guess regarding Asturian names – is as accurate as I can make it.

If I describe, say, a standing stone with Latin and Ogham inscriptions in a certain valley then you can trust that this stone not only exists but was found where I place it.

What places the book squarely in the realm of fantasy are the elements of Irish myth – the Tuath Dé and their Four Treasures (the Sword, the Stone, the Cup, and the Spear) – and Peretur’s uncanny connection to nature. In both the realistic and fantastic aspects of the book, nature plays a huge part; it’s what drew me to the Matter of Britain in the first place.

Ever since I got my first library card, I dragged home every piece of Arthurian fiction I could find. What I loved about books such as Rosemary Sutcliff’s Sword at Sunset and Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave was the landscape of Long Ago: the damp fecund earth, menhirs looming from the mist, and the sense of dark and tangled forest alongside every road; step off the path and into the wild.

What I did not love was never seeing people like me moving through that landscape: no queer folk, Black or brown people, realistic women (only women-shaped tropes), disabled people, or those born without privilege (except servants of those who mattered).

There’s a reason for that: the Matter of Britain is a national origin story, one made popular and used for centuries by (mostly) the English ruling class to justify their Empire and their colonialist tendencies (starting with Wales). Its straight, white, ableist privilege and sense of Manifest Destiny is essentially baked in.

Which is why, although I’ve loved reading these stories, I never imagined I would one day write one. Then Peretur dropped into my head and she – her name, how she grows up, what she can do – was my key to break open the fossilised shell of the legend and find a way around the problematic foundations of the National Origin story.

First, her name. Three of the Tuath Treasures – in the form of Excalibur, the stone it is pulled from, and the Grail – are easy to map onto Arthurian legend. The fourth, though, the spear, has no corollary. But etymologically, Peretur’s name could stem from two Welsh words, bêr, meaning hard or enduring, and hyddur, or spear. Peretur: Spear Enduring. Peretur could be the spear.

So now I could bring in Irish legend as well as Welsh history, and by adding two Pictish characters I enlarged the centre to include all the British, not just the colonising English.

Second, Peretur, in the later guise of Sir Percival, was raised in the wild by his mother. This was a perfect way to create a Peretur/Percival who was naïve: unaware of and untrammelled by the rules of power and privilege and other social guidelines. My Peretur had not spoken to a soul other than her mother before she left home, so had not been exposed to or absorbed any cultural bias. She could be poor, a woman, and love other women – all while being strong and utterly confident without feeling marginalised or inferior.

Finally, Peretur’s lack of interaction with other human beings – essentially raising herself, or perhaps being raised by the trees, birds, tastes on the breeze – has given her a profound connection with nature that allows her to do what others would consider uncanny.

Many readers would largely agree regarding which elements of the book to assign variously to myth, legend, or realism. But stale historiography – reliance on outmoded and outdated understanding of the past – may lead to one important area of disagreement.

Most artistic representations of the legend – literature, film, visual art, and music – are of wholly white, straight, cisgendered, and non-disabled people. But in Spear disabled, queer, Black, poor, female and gender nonconforming people exist. We have always existed. We are here now and we were there then – present in every corner of society in every era, part of every problem and its solution. No story without us is historically realistic.

I wrote Spear for people like me who want to see ourselves in a heroic past we’ve been told does not belong to us. This is why, to me, it does not matter whether or when Arthur and Camelot ever existed. To me, Camelot is not a particular place in a specific time. It’s a state of mind, a condition outside reality whose heroes fight, yes, but not for power over others. They fight to change the world in service of a dream of justice and inclusion, a dream of home and a place to belong.

Spear is for those of us who long not only to see ourselves in that heroic past, to not simply exist there but to thrive, to be the heroes.

Spear by Nicola Griffith is published in hardback on 24 May, 2022.

Nicola Griffith, a dual UK/US citizen living in Seattle, is the award-winning author of eight novels including Hild (2013), winner of the Washington State Book Award and named by the Sunday Times as one of the Ten top historical novels from the past ten years. A ninth, Menewood (the sequel to Hild), is coming in April, 2023.

Read more about Spear.

You may also enjoy Fil Reid‘s feature Who was King Arthur? And did he exist?

Images:

- King Arthur’s knights, gathered at the Round Table to celebrate the Pentecost, see a vision of the Holy Grail, Département des Manuscrits BNF Gallica, Français 116: Bibliothèque Nationale de France via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Cover of The Two Towers by JRR Tolkein, 1970s: Gwydion M. Williams for Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

- Cover of the first edition of Sword at Sunset by Rosemary Sutcliff, 1963: Wikipedia (to illustrate an article concerning the book in question)

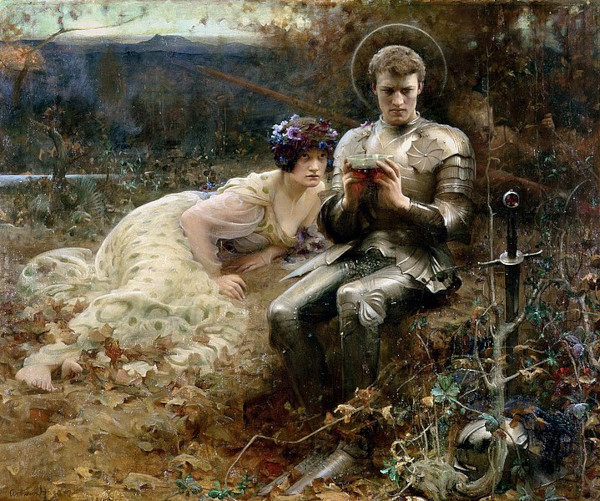

- Temptation of Sir Percival by Arthur Hacker, 1894: Leeds Art Gallery via Wikimedia (public domain)

- ‘King Arthur’s Round Table’, Winchester Castle: Rs-nourse for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- The Arming and Departure of the Knights, tapestry woven by Morris & Co for Lawrence Hodson of Compton Hall, 1895–6, from Burne-Jones by Christopher Wood: Wikimedia (public domain)