Eleanor Swift-Hook thinks it’s time we remembered the Dunkirkers, the most feared pirates of the early 17th century. Forgotten by most of us, these privateers operating in the English Channel were, in their time, the terrors of the seas.

My mistress, his good mother, with a daughter

About the age of six, crossing to Jersey,

Was taken by the Dunkirks, sold both, and separated…

No Wit, No Help like a Woman’s by Thomas Middleton

Forget the pirates in the Caribbean or the ones from the Barbary Coast: the most feared pirates in the first half of the 17th century were — Belgian!

A century before sailors were terrorised by the sight of the Jolly Roger’s skull and crossbones, they quaked in fear at the ‘Ragged Cross’ of the Dunkirkers.

In 1633 a priest recorded how a Dutch merchant vessel surrendered almost without a fight when the Dunkirker ship he was travelling on struck its false colours and raised its true ones. The cargo of just that one prize they took, timber and other goods, was worth at least a third of a million pounds in today’s reckoning.

The Dunkirkers were big business — entrepreneurial piracy. Behind each privateer ship was a group of investors who would pay for the vessel to be well equipped and crewed for its voyage (called a curso from which we get the term ‘corsair’), and who took shares in the plunder that the ship brought back to sell.

It was a maritime conflict conducted by private contractors. Far from being freebooting criminals, they were as much an instrument of war at sea as the famous and feared Spanish tercios were on land.

The core of the Dunkirkers’ fleet was a naval squadron of between 10 and 20 ships: the Armada of Flanders. The civilian vessels were well armed and licensed by the government of the Habsburg-ruled Netherlands and the Spanish crown. They took their prizes back to their home port and sold the ships and their cargoes, with a 10 per cent surcharge to government coffers.

Dunkirk was home to privateers even in the 16th century, but the real era of Dunkirker power was the 1620s–1640s thanks to a new kind of warship, developed and built by local shipwrights, that was specifically suited to northern conditions.

Nowadays, if we talk about ‘small ships’ in the same breath as a mention of Dunkirk, it conjures images of the flotilla of vessels that sailed from England to rescue troops in 1940 during Operation Dynamo.

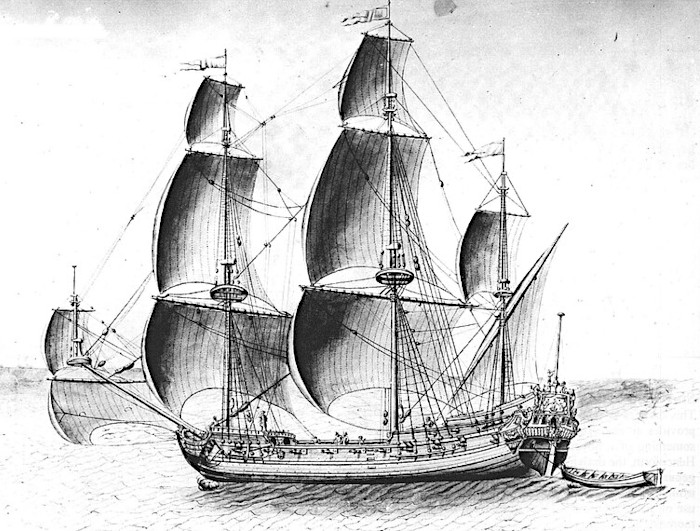

The implications of such words were very different 400 years ago. Because the ‘small ships’ that sailed from Dunkirk in the 1620s were the new fragatas (the name would become ‘frigate’ in English), uniquely designed small warships which could harness both wind and oar power at need.

Not all Dunkirkers were fragatas and sadly none appear in the few paintings we have that show Dunkirkers engaging at sea. We only have descriptions. From these we know they were narrower in the beam than other vessels and had a long and even deck, with no ‘castles’ fore or aft such as a galleon might have.

Low and sleek, able to carry 15–20 guns fired from the upper deck and with a single bank of oars, probably rowed from the main deck, they were deadly sea wolves who would hunt as a fleet, in pairs, or solo, wreaking havoc on Dutch and English merchant shipping.

Dunkirkers had a reputation for brutality worthy of the worst pirates. If they took a Dutch fishing vessel, they would often lock the crew in the hold and sink the ship. But the brutality was reciprocated. Dutch captains were required to vow to kill any Dunkirkers they took, throwing them in the sea, a practice that was known as voetenspoelen ‘foot-wetting’.

Both sides were so savage because the enmity between the Dutch and the Dunkirkers had a whole heap of history behind it. They were fighting each other in a religious civil war. Known to us as the Eighty Years’ War, it began in the mid-16th century and tore the Netherlands apart.

For the Seven Provinces of the Protestant Dutch Republic it was a fight for survival; for those in the Habsburg ruled Catholic lands, a war against dangerous heretical rebels. In such a conflict there was little room for mercy.

But there was occasionally some shown on both sides. Women were seldom ‘sold’ in the manner Thomas Middleton suggests, and could usually hope to be treated well. Dutch sailors were sometimes taken as prisoners and released if fees were paid or in the occasional prisoner exchange. Captured Dunkirkers might be given their ‘foot-wetting’ by being placed on one of the offshore shoals from which they could swim to shore.

And, of course, the wealthy on both sides could expect mercy if the prospect of a large enough ransom was on offer.

To counter the threat posed by Dunkirk, the Dutch sought to maintain a permanent blockade of the port, though that was never completely effective and not without risk.

In 1625 an unseasonably early October storm devastated the blockading force, sinking or scattering all but a handful. The gleeful Dunkirkers poured out to lay waste to the unprotected Dutch fishing fleet and any unfortunate merchant ships they encountered. In the space of a fortnight 150 Dutch vessels, including 20 warships, were captured or sunk.

It was to avoid such storms that in November each year the Dutch were forced to withdraw and order their fishing fleet back to port, freeing the Dunkirkers to roam the Narrow Sea (the Channel) and the German Ocean (the North Sea).

The long winter nights and the uncertain seas allowed fragatas to hunt with near impunity, their low profiles invisible in sea mist and their oars giving them manoeuvring advantages and speed their sail-reliant prey could not match.

The Dunkirkers’ privateering licence extended to all vessels carrying supplies and victuals to the Dutch, including English ships. Between 1625 and 1630 one in every five merchant ships sailing from England would fall victim to a Dunkirker. A major reason Charles I had to raise his infamous Ship Money was to pay for a navy to protect against that.

Not all English encounters with Dunkirkers were hostile. In 1623, on his way home from Spain, Prince Charles (who would become Charles I) encountered a sea battle where “certain Dunkirkers and Hollanders were at it pell-mell.”

Inviting the captains from both sides to come aboard his ship, his highness “told them that since it was their good fortune to fall into his company, he would persuade them to be at peace” and he “prevailed so much… that they parted friends.”

The Eighty Years’ War ended in 1648, but when war broke out between Cromwell’s Protectorate and Spain, the Dunkirkers sailed again. As before, they devastated English shipping.

Perhaps they were too effective for their own good. To stop their predations, a combined English and French attack was mounted, capturing the port in 1658 and ending the Dunkirker threat to England once and for all.

But the old tradition of privateering enjoyed one final reprise. Now part of France, when Franco-Dutch hostility broke out in the 1670s, Dunkirkers sailed against the Dutch again.

The final blow was dealt only in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht. The terms of that treaty required the destruction of the jetties, defences and port facilities in Dunkirk, and meant that after over a century of piratical plundering, privateering Dunkirkers could no longer take to the seas.

The Soldier’s Stand by Eleanor Swift-Hook is published on 25 February, 2025. It’s the second in her Lord’s Learning series.

The Dunkirkers feature in the first book, The Fugitive’s Sword.

Eleanor is an expert on the social, military and political events that unfolded during the Thirty Years’ War and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. She lives in County Durham.

You may enjoy reading our interview with Fiona Forsyth and Eleanor Swift-Hook.

Historia features on related topics include:

On 17th-century wars:

Nördlingen, a town where history is past and present by JC Harvey

Fiction and the English Civil Wars by Jemahl Evans

Charles I – the boy who would be King by Mark Turnbull

The never-ending Battle of the Boyne by Angus Donald

Our interview with Minette Walters

On naval warfare:

The Protestant Wind by Maggie Craig

(Re)writing the Spanish Armada and Are we the bad guys? Writing naval historical fiction from the French point of view by JD Davies

Reassessing Francis Drake: what research for my novel revealed about his role in the slave trade by Nikki Marmery

England’s First Great Naval Victory by Catherine Hanley

Was King Alfred really the father of the English navy? by Chris Bishop

Images:

- Witte de With’s Action with Dunkirkers off Nieuwpoort by Jacob Gerritsz Loeff, 1643: Royal Museums Greenwich via Wikipedia (public domain)

- Jacob Collaart, privateer, before 1637: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Frégate a la Voile, light frigate under sail by Nicolas de Poilly, c1675–80: Bibliothèque nationale de France (public domain)

- The Surrender of Breda by Diego Velázquez, c1635: Prado via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Bombardment of Dunkirk by a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet, c1700: Wikimedia (public domain)

- View of Dunkirk from De praecipvis totivs Vniversi vrbibvs, liber secvndvs by Georg Braun, 1575: National Library of Poland via Wikimedia (public domain)