Essie Fox writes about the Victorian obsession with human anatomy — often as grotesques — and the bizarre tale of one museum owner whose success resisted scandals and attempts to close his establishment for years. It’s part of the background to The Fascination, her latest book.

My new novel, The Fascination, is a Victorian gothic set in the rural fairgrounds, the glamour of the London theatres — and an anatomy museum based on one that did exist in a shop in Oxford Street. The true facts about the venue were a gift to my plot, and though my shop proprietor is only vaguely based on the famous Dr Kahn, the antics of the real-life owner could easily inspire a novel of his own.

Dr Joseph Kahn’s Anatomical and Pathological Museum proved to be a successful London tourist destination, running for 22 years from the day it opened up in 1851. Despite being described as a gloomy sepulchre of pathological horror there was enormous public interest, aided by adverts such as this one in the Daily News:

DR. KAHN’S GRAND ANATOMICAL MUSEUM, 315 Oxford Street, is now OPEN from 10 o’clock in the morning till 10 o’clock at night. Popular Lectures, explanatory of the Structure and Functions of the Human Body, and illustrated by models, will be delivered daily by an English medical gentleman, at the following hours, viz., 11,1,3,5,7, and 9 o’clock – Admission 2s.

Visitors who took the bait to visit the museum would be shown Kahn’s displays of the ‘sacred body beautiful’. Some may have learned the facts of life from the models on display, or else been lectured on the dangers to the lungs from heavy smoking.

There was also the rejection of what, at the time, was commonly believed to be a genuine condition called ‘maternal impression’, whereby abnormalities occurring in the human body were often caused by pregnant mothers having witnessed shocking scenes.

(This was the reason often cited by Joseph Merrick‘s family for the disfiguring tumours that grew over his body after his mother was knocked down by a fairground elephant while she was carrying her son. Later, when Merrick toured as an exhibit in freak shows it was under the guise of The Elephant Man.)

A museum such as Kahn’s was not entirely new. The general public often gathered in great numbers to observe the anatomical figures at Simmons’s Waxworks in High Holborn. A source of lurid wonder was their model called Samson whose torso opened up to reveal internal organs.

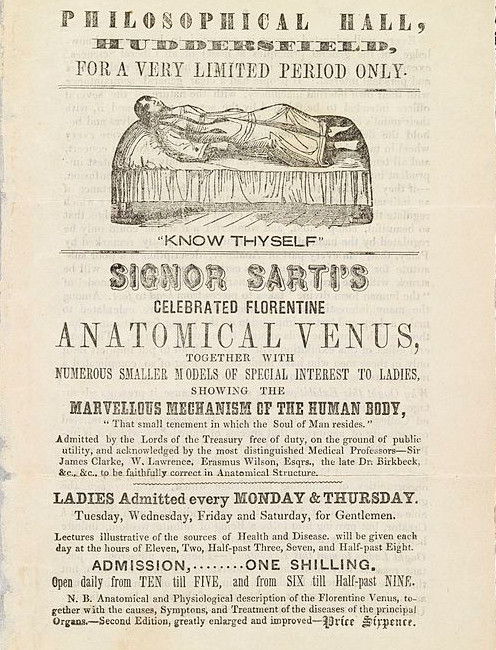

Similarly, Signor Sarti‘s exhibition in Margaret Street had a wax Venus and Adonis – ideas that Kahn was to follow with his own grand displays of anatomical, surgical, and embryological collections. He was keen to emphasise the scientific elements, recommending the exhibits for entire families, or even visits from school children.

Thankfully, the dire effects of venereal disease were kept concealed in private rooms, left only for the eyes of trainee medical men. However, in reality, any adult with the means to pay the entrance fee could go inside and take a look, which in turn led to the Lancet expressing grave concern that many female visitors were being exposed to sexual depravities.

When Dr Kahn then insisted that any females were there in a professional capacity, being midwives or nurses, the editor was satisfied at the value of the show, even going so far as to recommend the venue as a source of valid learning.

More threats were to come from Kahn’s competitors. Owners of Reimers’s Museum encouraged a young boy to formally complain that Kahn had ‘interfered with him’.

Once again, it was The Lancet which came to Kahn’s defence, although it claimed disappointment when Kahn went on to promote the sales of quack medicines.

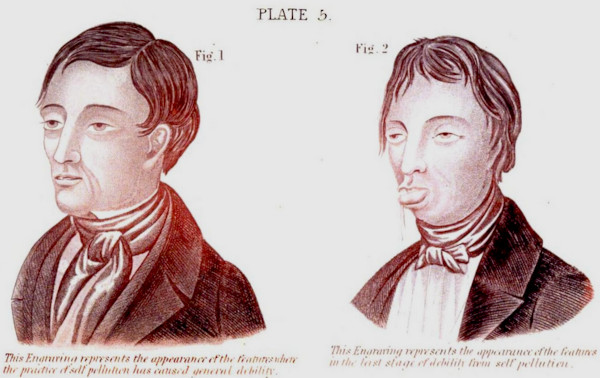

The Jordan family, operating as Perry & Co, were closely linked with the business. Mostly known for their ‘cures’ for venereal disease, they also made appliances for the treatment of young men suffering from ‘spermatorrhoea’, or ‘states of nervous exhaustion’ brought on by the rigours of too frequent masturbation.

This business was lucrative. Soon Kahn rented a lavish home for himself in Harley Street and he rode about the city in his own private carriage. The museum itself was moved to Piccadilly, which proved to be the final straw for the medical profession.

Kahn was eventually charged and taken to court where it was found he had no right to call himself a doctor. Representatives of The Lancet also claimed that his displays were sordid and immoral, with books and pamphlets bordering on being pornographic.

Even during this upheaval Kahn continued selling guides on sexual health, diet, and hygiene. He also gave lectures on human curiosities — such as humans growing tails discovered in Africa, or the remains of a child that had been born with several legs labelled as The Heteradelph.

But by 1864, the General Medical Council struck at the business once again, with Kahn accused of illegally working in and running an unlicensed medical practice. At this point he disappeared and was never seen again.

Still the museum did not close. The Jordans carried on selling quack goods and medicines, even using Khan’s name to promote a new museum opened up in New York.

However, back in London they were vigorously hounded by the Society for the Suppression of Vice.

Following yet another court case it was demanded all their stock and exhibitions be destroyed. Somewhat dramatically, the solicitor representing the Society’s case was then personally allowed to take a hammer to the models, breaking up what The Times went on to describe as being items of “the most elaborate character… said to be worth a considerable sum of money.”

What would we make of them today?

The Fascination by Essie Fox is published on 22 June, 2023. It was listed in The Sunday Times as one of Nick Rennison’s Finest New Novels.

Read more about this book.

Essie would like to thank the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine and the Wellcome Collection for invaluable information.

You might also enjoy Essie’s feature The Victorian theatrical world of mystery and illusion.

If the history of medicine interests you, you might like these features:

Elizabethan medicine: spectacularly wrong – and likely to kill you by SW Perry

Witch’s Mummy: corpses and cure-alls by Naomi Kelsey

Health and Hellfire: Personalising the Plague in 17th Century London by Deborah Swift

Plague and pandemic: how we responded then and now by Anna Abney

The Darker Quacks – Between folklore and science by Oscar de Muriel

Images:

- Main body of wax anatomical model of reclining woman with removable internal organs, probably from Florence, late 18th century: © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- Dr Joseph Kahn, lithograph: Wellcome Collection 4956i (public domain)

- Signor Sarti’s celebrated Florentine anatomical Venus, 1849–54: Wellcome Collection (public domain)

- The appearance of the features where the practice of self-pollution has caused general debility/in the last stage of debility from The Silent Friend by R and L Perry & Co, 1847: Google Books (public domain)

- The Heteradelph; or, Double-Bodied Boy by Joseph Kahn, MD, after 1857: Wellcome Collection (CC BY-NC 4.0)